Gwen Nelson

Gwen is an experienced English teacher who teaches in the West Midlands and has taught in a variety of school settings. Gwen has also spent time in the FE sector teaching a range of A-Level courses to 16-19 year olds, with A-Level Language and Literature becoming a specialism. She has recently returned to the secondary sector, and has had a somewhat interesting year which has involved answering the bat-signal for day to day supply. Her writing has been published in books ‘Don’t Change the Lightbulbs’ and ‘Dual Coding with Teachers’ as well as Oxford English Blogs. She will soon be published by Routledge in a book for, and written by A-Level Language and Literature teachers.

I have taught this text repeatedly for AQA’s Language and Literature A-Level in an FE setting, and for the legacy AQA Literature A-Level unit on The Gothic (which resulted in me teaching Frankenstein twice in one year, for different A-Level courses). Each year you teach the same text, something new is noticed, or revealed, and your knowledge of the text grows.

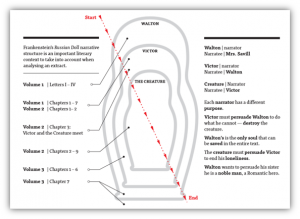

In order to explore Walton’s narrative, the global narrative structure – Shelley’s ‘Russian Doll’ layered narrative, must inform the discussion. Walton is the ‘framing device’ that follows the older, established Gothic conceit of the found manuscript – akin to the found footage cinema such as The Blair Witch Project (1999), and the Paranormal Activity franchise (2007, 2012). Shelley, as Shelley would, evolves the ‘found manuscript’ conceit and instead we have a ‘found narrator’ when Walton happens upon Victor Frankenstein while his boat is trapped in the ice.

| Diagram by kind permission of @olicav |

The novel opens using a well-known form of novel writing – epistolary fiction. It is this choice of form which gives this narrative, and Shelley’s predecessors something that in Film and Media Studies courses would be called ‘verisimilitude’, or audience believability in lay-man’s terms. The use of a non-fiction form of writing to construct a fictional narrative is the earliest form of novel writing – Richardson’s Pamela (1740) is the most notorious early example of this –so is an astute use of the form by Shelley. The audience for the novel is initially on familiar territory as soon as they notice the epistolary form. This then elides into a format of volumes and chapters which is the kind of novel format we, as modern readers, are familiar with. The epistolary form book-ends the whole narrative, so giving it a sense of authenticity, even if that authenticity is as constructed as everything else within the text.

Key Question: What is the difference between the Romantic and Gothic sublime?

The simplest way I articulate these concepts to students is that the experience of the Romantic sublime (nature in all its magnificent glory) is a spiritual and healing experience, and we see the effects of this form of the sublime at numerous points in Victor’s narrative. Here a picture of Snowdonia, in uncharacteristically warm and sunny weather, will suffice for an illustration of the Romantic sublime:

Conversely, the Gothic sublime is a different kind of magnificent nature. It can kill you. This Swiss alpine glacier and mountain range is standing in for the treacherous arctic that Walton desires to ‘conquer’ (By kind permission of Daniel Simcox).

Conversely, the Gothic sublime is a different kind of magnificent nature. It can kill you. This Swiss alpine glacier and mountain range is standing in for the treacherous arctic that Walton desires to ‘conquer’ (By kind permission of Daniel Simcox).

In a Gothic text, one should never be complacent about the author’s use of setting, and none more so in this text. The fact that our found implied narrator is located in the most treacherous of Gothic sublime locations is Shelley’s less than subtle hint of the reckless Promethean qualities Walton currently, i.e. in the novel’s present, shares with our soon to be discovered second narrator Victor.

Walton’s narration envelopes that of Victor and the Creature’s, but to write off Walton’s narration as a mere literary conceit does it a disservice, it achieves a great deal more than that. He too has some significant character development which is symbolised by his starting point of being trapped in the ice with his crew.

At the start of the novel, letters 2 and 4 show us, without any real subtlety, what to be trapped in the Gothic sublime is:

Letter 2

To Mrs. Saville, England

Archangel, 28th March, 17—

How slowly the time passes here, encompassed as I am by frost and snow!

Letter 4

To Mrs. Saville, England

August 5th, 17—

Last Monday (July 31st) we were nearly surrounded by ice, which closed in the ship on all sides, scarcely leaving her the sea-room in which she floated. Our situation was somewhat dangerous, especially as we were compassed round by a very thick fog. We accordingly lay to, hoping that some change would take place in the atmosphere and weather.

This edited wide angle shot of a Swiss glacier and open skies shows the kind of blank open vista that sent both the Ancient Mariner and Walton to their depths of despair (by kind permission of Daniel Simcox).

In the latter version of her text, the allusions to Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner can be drawn out without the danger of upsetting literary historians. The parallels between the setting of the opening of the novel, and Coleridge’s Gothic ballad, Part 1, Stanza 15 and Part 2 Stanza 8, are quite obvious:

Part 1, Stanza 15:

The ice was here, the ice was there,

The ice was all around:

Part 2, Stanza 8

As idle as a painted ship

Upon a painted ocean.

The imprisonment and entrapment of Walton and his crew by the ice, one could argue, symbolises Walton’s own entrapment created by his Promethean, hubristic flaw. He has the potential to be as foolish as Victor Frankenstein, unless he has the capacity to learn. The Gothic sublime also illustrates the reason for his shared loneliness with Victor and the Creature, and why he comes to adore Victor. The ‘chance’ (of course it’s not chance, Shelley constructed this ‘chance encounter’) meeting of Victor and Walton offers the only opportunity for Walton to escape the crushing ice, and metaphysically grow into a better person than Victor – which, given the low bench-mark Victor sets, shouldn’t be too difficult. There are some clever practical achievements to this narrative conceit; the entrapment enables the epic and melodramatic narrative of Victor, and the Creature to be told with little interruption. It is a fine and practical method to enable the convergence of all three narrative voices and points- of- view to occur in the narrative.

Key Question: Why MUST Victor tell his narrative to Walton? What is the purpose and significance of this?

The answer to this lies in the novel’s subtitle ‘Or the Modern Prometheus’. Shelley’s text has a didactic purpose in the same way the Greek Myths did. Sometimes the mythological narrative is a way to try to explain how the world worked, to answer questions like ‘Why do we have day and night time?’ ‘We have four seasons, but why?’. The mythological and Biblical narratives also explored philosophical issues of not just who we are, but why we are and to do achieve their aim, they are also didactic. They are to teach us moral and ethical codes, and that should we break the codes, ignore the lessons, our hubris will be punished. Shelley revises this mythological form to create a didactic text for her contemporary audience. Walton must learn, and as we are positioned with him, we must learn not to fall prey to our own hubris. We will be punished, our souls will be damned. Walton’s soul must be saved, or the creation of the Creature, and the loss of the entire Frankenstein family, is for nothing.

Walton in the classroom

Before getting into the text, some useful pre-reading are some Greek myths that inform the whole narrative and the trajectory of the characters: Prometheus, Narcissus, Pandora, Theseus and the Minotaur (for the concept of the labyrinth which is also a cornerstone Gothic writing). The most obvious to start with is Prometheus, because the subtitle of the novel is ‘or the Modern Prometheus’ which is meaningless unless students are explicitly taught this myth. It is alluded to frequently in the novel, and very much so in Walton’s letters at the start because we are meant to see similarities between Walton and Victor, even if they themselves can’t.

Next, explicit teaching of the global narrative structure is vital, or the ingenuity of Shelley’s ‘Russian-doll’ structure, the polyphonic narration and Walton’s place within it (technically ‘without’ it, as he frames it) is lost and students will battle with the text more than they need to.

Finally, choose sections of a letter or letters to analyse in depth, and I will obviously bias a ‘LangLit’ or Stylistic approach here, such as the following:

Extract: Walton’s Letter 2, using the first and last paragraphs.

The context in which I would have taught this is fairly early on in the LangLit A-Level, where the key concepts and language levels are being explicitly taught, so the reading and analysing the text allows students to apply these new and scary concepts to extracts of an exam set text. Here the focus was on Shelley’s lexical choices, with a wider focus on reader positioning:

- How does Shelley position us with our narrator Walton?

- Why do you think she does this?

- Find the a) abstract b) concrete and c) proper nouns in the text. What do you notice about the frequency of each? What might this reveal about Walton as a narrator (and character)?

- Next look for the choice of verbs (material, relational, mental and verbal):

What kind of verb processes dominate this extract? Why do you think this is? What effect do you think this has? Is Shelley’s emphasis like Bram Stoker’s ‘Dracula’– focused on action? Or not? Explain and discuss your findings in detail.

- Noun-phrases e.g (a phrase built around a noun) –does Shelley use these too? Are they frequent, or infrequent? Why is this?

- Finally, seek out Shelley’s range of modifiers: adjectives and adverbs (base, comparative and superlative). What is the most common kind? What is the least common kind? Why do you think this is? What might the intended effect be?

As you can see the questions DO ask students to identify using terminology as this is a big assessment objective in a LangLit (and Language) A-Level, but the main purpose of this is getting students to look for and find patterns in language, then we can get into how such patterns make meaning. Patterns can also be used to identify larger structures, or elements of the structure of the narrative that we would not have paid attention to before.

Later on in an A-Level course, layers are added to the demands of analysis, so when revising this in the second year, grammar, semantics, phonetics and so on would all be applied to set text extract analysis. Students, of course, must always view an extract as part of a whole, which is where the key questions in this blog come in – which themselves draw attention to the purpose of Shelley’s techniques as a storyteller. Posing ‘bigger picture’ key questions to frame the teaching of Walton’s narrative provide a means for students to put their learning in context of the text, and the A-Level course as a whole. Furthermore this switch between micro, macro and big-picture analysis neatly prepares students for the demands of an A-Level exam question.

Admittedly, this may appear to be an awful lot of leg-work for something – Walton’s narrative – that on the surface appears to be not terribly significant to the novel as a whole. However, only by paying Walton and his letters due attention at the start, can we fully understand the narratives of Victor and the Monster, the purpose of Shelley’s story and the catharsis that comes when the novel comes to its desolate and dramatic conclusion.

Recommended further reading:

Barry, P. (2009). Beginning theory. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Chaplin, Sue (2011). Gothic Literature: York Notes Companions. London, Longman

Giovanelli. M. and Harrison.C. (2018). Cognitive Grammar in Stylistics: A Practical Guide. London. Bloomsbury.

Giovanelli, Marcello. (2018); The Language of Literature (Cambridge Topics in English Language). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Giovanello, Marcello. (2018). Narrative (Cambridge Topics in English Language). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.