Kiwi-born singing grammar guru Jill Reynolds works in a new academy in Greater Manchester. She has been teaching for 11 years, has set up and established a university-style club for high achieving KS4 students, teaching higher level students the fundamentals of rhetoric and aspects of literary feminism, realism v. idealism etc, and is passionate about effective revision and Shakespeare – amongst other things!

Take one whole Shakespeare play, up to 3 hours performance length in total, adding a ‘judicious’ smattering of contextual detail. Marinade in knowledge of themes and characters. Grate into memorable quotations, grill students on their recall and simmer for 20 minutes until it produces a ‘clear’ essay, distilling down the deep flavours of the whole play into a meaning-rich discussion of a theme or character.

Part B – the part of the Shakespeare assessment that is assessed for a student’s knowledge of the themes and characters of a play – can seem a daunting prospect, and rightly so: trying to tie down the key elements of a Shakespeare play can feel like trying to lasso a cloud. Shakespeare plays have endured through the centuries because they are complex – every person who goes to the theatre to see these plays will find a character or a storyline that they can identify with. Like the cooking metaphor I’ve used (badly) in my opening paragraph, every element of Shakespeare brings flavour, and even Heston Blumenthal would struggle to isolate every subtle influence, every nuance.

So thanks, Jill – you’ve reinforced what I’ve already understood clearly: this is a challenging question and trying to pin Shakespeare down to easy definitions of meaning is nigh on impossible.

But this is the right starting point – Shakespeare is complex, and our students need to grasp that to write effectively about any play. And arguably, this is what makes the plays entertaining and engaging: as teachers, every time we revisit the plays we see new ideas, and we shouldn’t shy away from that. Every play Shakespeare wrote has a paradox at the heart of it, a challenging truth – so that is my starting point.

Is Macbeth a suggestible man who falls under the influence of powerful women, or a bloodthirsty opportunist who reads the signs to benefit himself?

Do Romeo and Juliet gravitate towards each other because they are fated to be together, or is every tragic step a choice?

Complexity is what allows discussion – multiple perspectives are helpful!

For the rest of this blog, I’ll be using Romeo and Juliet as the basis of my approach for pinning down this question, but trying to outline principles that can be applied to any play.

Step 1 – Create a timeline of the play.

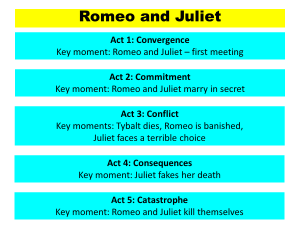

Start with summaries of the acts. Wherever possible, try to write these yourself, but use the online summaries to help you to pin it down. Below is a basic summary of the plot of Romeo and Juliet as an example:

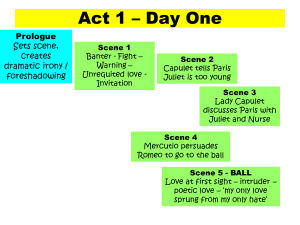

This is obviously a starting point, but it helps to frame the events of the play. From here, you can make maps of the acts – see next image for Act 1 of Romeo and Juliet.

At this point, even without specific quotations, students can begin to identify key moments, cause and effect, themes and characters.

When you are creating your timeline, look for the patterns of the play – for example, in Romeo and Juliet, the most significant scenes occur at the beginning and the end of each act. The masked ball of Act 1 Scene 5 is pivotal in the play: Juliet chooses Romeo over Paris, Tybalt swears revenge (which culminates in his death and Capulet’s change of heart over the timing of Juliet’s marriage to Paris) and the inevitable path towards tragedy begins. It becomes much easier for pupils to spot the ‘cause and effect’ detail in the play.

Step 2 – what makes a useful quotation?

In the mark scheme, quotations and references are acceptable – however it will always be more impressive to use quotations, and this has to be the goal. Certain quotations fit a multitude of purposes because they fit a range of essay types. These ‘super-quotes’ are well -worth committing to memory.

My first stop for choosing quotations is the frame for each question: what are the themes and who are the characters?

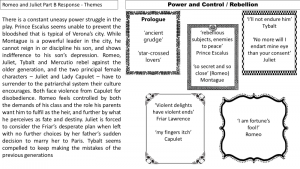

Themes in Romeo and Juliet: family relationships (gender roles, power and control, parents), romantic love (idealism/realism, worship), religion and faith, fate and destiny, anger and violence (conflict), etc.

Consider this quotation from Act 2 scene 6, Romeo and Juliet’s secret marriage:

Friar Lawrence: ‘violent delights have violent ends’ – Act 2 Scene 6

My character is Friar Lawrence, father-surrogate to Romeo, and confidante to both of the lovers – his authority seems to outrank that of Montague and Capulet, and his desire to break the feud makes him decide to be a co-conspirator in the marriage. Immediately, this seems like a prophetic statement: it seems a fitting description of the escalating vicious cycle of violence that ensues in the next act, so this immediately triggers ‘FATE and DESTINY’ and ‘VIOLENCE’ in my mind. But this is a wedding, and the Friar is describing LOVE – whatever we pursue too aggressively will bring conflict, and even love leads to violence in this distorted society.

I think – feel free to shoot me down on this – it is far better to consider quotations in sequence, as this helps to establish where the ideas fit into the narrative, and will help students to describe why these moments are significant.

It’s helpful, at least to start off with, to supply the quotations, as in the slide below:

In Romeo and Juliet, most themes start in the prologue, so I encourage students to learn the prologue off by heart (yes, really).

Step 3: Framing an answer

This is the point where students’ eyes glaze, there is much surreptitious nosing at neighbours’ answers, and finally a coy hand raised: ‘what are we doing?’

The question is asking students to discuss and describe why a theme or a character is central to the play:

- What ideas does Shakespeare present about this person / theme?

- What effect do these have on the story?

- How does this reflect the time when the play was written?

- What reaction does this provoke?

After repeatedly and thoroughly teaching PEE and variations of language analysis, when it comes to this type of questions, my students struggle to know what to say. For this reason, I’ve used playing card symbols to categorise the comments students can make:

There is a natural progression to teaching this section – live WAGOLL paragraphs (writing the perfect paragraph with pupils), identifying the sections of a WAGOLL paragraph matched to the criteria, ‘WAGOLL or WABOLL’ (is this a good example or a horrible warning?), and finally improving a WABOLL (What A Bad One Looks Like). All of this can develop student confidence and ability to work independently.

Step 4: Higher level responses

This will ultimately depend on your class. Some of the most perceptive comments I have heard from pupils have come from lower ability candidates – emotional intelligence can go a long way in developing concepts and descriptions of these characters and their motivations. So here are some ideas that have helped to develop my able students.

Character flaws

Get students to discuss what the tragic flaws are in the characters – what ultimately leads them to make their mistakes? For example, Romeo describes love as ‘a smoke’, and this is exactly what it is for him: it stops him seeing things clearly, it leads to tears, it’s hard to get hold of, and too much will kill him! What makes these characters destined for their outcomes? What are their strengths and weaknesses?

Static and dynamic characters

Some characters are locked into a repeating pattern of behaviour – consider Tybalt. From the outset, he is defined by violence, and it will characterise every time he occurs in the plot. He cannot / will not change, reflecting the rigid honour-based Verona culture, and this is what Shakespeare develops through him. However, some characters are developed through circumstances – consider Capulet. Love him or hate him, Capulet is a complex character: he wants to be the loving father Juliet needs, but with Tybalt’s death, he faces the logic of necessity – he needs an heir to ensure the family’s future, and this brings his plans forward. He also finally learns the lesson of his daughter’s death, paying the ultimate price for his actions.

Escalation and de-escalation

In any narrative, action escalates towards a climax and culminates into a conclusion. Getting students to comment on how key moments and ideas contribute towards this journey will lead to more complex and effective discussion.

Unanswerable questions

Get students used to debating perspectives – then flip opinions. A lot of key understanding and conceptual development starts out in conversation, so giving students those paradoxical questions to discuss and take a position on will develop their ability to describe them in their writing.

Ultimately, what we all know to be true is that we teach better when we are teaching something we love. Shakespeare is a master of provoking strong responses, and it is these strong sympathies and antipathies that make a text exciting and engaging. It is well worth the time you spend in preparing a play, because your own responses and reactions will shape those of your students, and their enjoyment of the text.